Niger J Paed 2014; 41 (4): 331 - 336

ORIGINAL

Ahmed PA

Clinical presentation of

Ulonnam CC

tuberculosis in adolescents as

seen at National Hospital Abuja,

Nigeria

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v41i4,8

Accepted: 3rd May 2014

Abstract

Background: Adoles-

clinical symptoms while 2(5.6%)

cents with tuberculosis (TB) form

were

asymptomatic;

identified

Ahmed

PA

a

significant proportion of child-

during contact tracing as latent TB

Ulonnam CC

(

)

hood

TB cases presenting with

infection (LTBI). Abnormal chest

Department of Paediatrics,

specifics clinical patterns.

radiograph findings were; wide-

National Hospital,

Objective: To

describe the

clinical

spread lung infiltrate in 10(27.8%),

Abuja Nigeria.

hilar opacities 7(19.4%), cavita-

Email: ahmedpatience@yahoo.com

presentation of tuberculosis in

adolescent at National Hospital

tory lesions 4(11.1%), pleural

Abuja (NHA), Nigeria.

Effusion 3(8.3%) and military

Subjects and method: This

is a

opacities 1(2.7%). AFB was

descriptive

and

retrospective

isolated in 5(13.9%), while

study of adolescents aged 10- 15

23(63.9%) had a raised ESR above

years seen at the department of

30mm/hr. Twenty seven (75.0%)

Paediatrics NHA Nigeria from

of

the adolescents completed treat-

August 2009 to July 2013.

ment for tuberculosis, 7(19.4%)

Result: Thirty-

six adolescents

were lost to follow up and

diagnosed with tuberculosis were

2(5.6%) died while 4(11.1%) had

reviewed.

Adolescent

TB

ac-

re-treatment for TB from relapse.

counted for 18.8%(36/192) of

Clinical presentations were pulmo-

total cases of children aged 0-

nary TB (PTB) 22(61.1%), and

15years seen at the Department of

extrapulmonary TB

12(33.3%);

Paediatrics

Respiratory

Clinic

distributed as TB adenitis

during the study period. The mean

4(11.1%), TBM 3(8.3%), Pericar-

(SD) age was 12.3(1.76) years.

dial TB 3(8.3%), Miliary TB

Twenty seven patients (75.0%)

1(2.8%) and Spinal TB 1(2.8). Of

were females and 9(25.0%) were

the nine with HIV- TB coinfec-

males. Thirty

(83.3%) were of

tion, the clinical presentation were;

lower socioeconomic class. His-

PTB 5(55.6%), and

tory of contact with a case of TB

extrapulmonary 4(44.4%).

was obtained in 17(47.2%). The

Conclusion: The

patterns of

TB in

commonest symptoms identified

adolescents are admixture as seen

in

these adolescents were; cough

in

younger children and adult from

27(75.0%),

weight

loss

22

clinical and radiological character-

(61.1%), fever18(50.0%), sputum

istic findings. TB remains a pre-

14(38.9%), body swelling

ventable disease condition and is

7(19.4%), hemoptysis 2(5.6%);

curable

with early appropriate

while signs were underweight,

treatment

pyrexia and chest findings. Nine

(25.0%) had associated retroviral

Key words :

Adolescent tuberculo-

disease. Thirty four (94.4%) pre-

sis, clinical pattern.

sented at time of diagnosis with

Introduction

bers of the general population

2,3 . In 2012, WHO esti-

mates that 8.6 million incident cases of TB were re-

The adolescent person whose age is between 10 -19

ported with 530,000 new case of TB being children less

than 15 years and 74,000 child deaths from the disease .

2

years, has been described generally to be a healthy

group compared to the general population, despite their

These estimate were higher than the report published in

known high risk behavior . The adolescent who is also a

1

the preceding year reflecting that more TB cases were

being notified among children globally . Over 30

2

young person suffers from TB along with other mem-

332

million Nigerians (approximately 22 percent) are be-

The protocol for diagnosis of tuberculosis in the clinic

tween the ages of 10-19. The adolescents and Young

4

were based on:

people represent a high risk sexual behavior groups that

are

highly vulnerable to HIV /AIDs infection and conse-

Bacteriological identification of mycobacterium tuber-

quently at risk of TB, in the dual pandemic .

5

culosis complex by direct smear microscopy performed

using auramine-rhodamine and confirmed with Kinyoun

The

younger child, under five have been shown to be at

stain on clinical specimen in a patient with suggestive

greater risk of TB especially in the presence of malnutri-

symptoms and signs or

tion

and lower family socioeconomic background .

6,7

Clinical diagnoses based on a combinationof symptoms

Childhood TB cases proportions in countries vary from

and

signs in the presence of any one or more of the fol-

3-

40percent . Nigeria is among the 22 high burden

2

lowing; a tuberculin skin test (TST) ≥ 10 mm for patients

nations with TB, accounting for 80percent of the world

that are HIV negative or >5 mm in HIV positive pa-

TB

cases. An estimated 1.1 million (13percent) of the

tients, a history of contact with suspected tuberculosis

8.6 million people who developed TB in 2012 were HIV

patient, radiological and/ or histo-pathological finding

positive with 75 percent in the African region . This

2

from lymph node biopsy suggestive of TB. Such clini-

ancient and still ongoing TB scourge is caused by the

cal features include a history of cough lasting for two

mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, with

high and

weeks or more, sputum with or with haemoptysis, pro-

low prevalence worldwide despite available measures

longed fever for which patient has been treated with

that highlight how to addressed and control the disease.

8

antibiotics with no improvement, weight loss or malnu-

9

The young person will be at risk of TB infection when

trition and poor appetite. Other symptoms include con-

in

contact with a case of TB disease who is actively

vulsions, loss of consciousness, swelling in the back or

coughing, especially when he is immune compromised,

any other part of the body. Signs recorded were also

is

homeless or lives in congested camps, prison or jail,

retrieved including laboratory test results, treatment

or

nursing home and have risky behaviors such as intra-

given with duration and outcome. Cultures were not

venous drug use

2,

3

.

done on any of the specimens. Only children aged less

than 16 years were seen at the paediatric respiratory

There are few reports that have focused on TB burden in

clinic as part of the hospital policy, while those 16 years

the adolescent. In the United States, adolescents com-

and above were attended to by the adult physicians.

prised approximately one-third of the pediatric cases

reported from 1994 to 2010 . The younger child, par-

3

A

proforma was used to extract information relating to

ticularly the under-fives play little role in the transmis-

patient demography, clinical symptoms and signs, his-

sion of TB because they more often have negative

tory of contact, pattern of TB, radiological features,

smears; they rarely have cavitary disease; they often

treatment and outcome (completion of treatment, lost to

have little or no cough; and when cough is present, it is

follow up or retreatment for TB). All the patients were

generally not forceful enough to expel aerosolized ba-

under care by the authors and case folders retrieved were

cilli efficiently.

10

In

contrast, the 10- to 19-year age

analyzed after approval was obtained from the institu-

group presents a different spectrum of disease manifes-

tional review board of the National hospital Abuja. Data

tations, including adult-type disease, from which respi-

were analyzed using Microsoft excel 2010 and mean

ratory samples can be more readily obtained . The Stop

2

(SD), percentages and tables were generated.

TB

Partnership goals include reducing the global burden

of

TB (prevalence and mortality) by 50 per cent in 2015

compared with 1990 levels and eliminating TB as a pub-

lic health problem by 2050 . In other to achieve this

11

Results

goal, the adolescent though largely a subset of the paedi-

atric age group but differ remarkably from the younger

A

total of 52 adolescents aged 0-15 years diagnosed

child should be viewed differently since preventive

with tuberculosis were documented in the paediatrics

measure for TB differ for the child and the adult.

respiratory clinic record, but only 36 case folders with

The study aims to describe the clinical presentation and

adequate information retrieved from the hospital medi-

outcome of adolescent tuberculosis at National Hospital

cal records were analyzed during the period August

Abuja (NHA), Nigeria.

2009 to July 2013. This gives a prevalence rate of 18.8%

(36/192). The mean (SD) age was 12.3(1.76). 75.0% of

the adolescents were females while 83.3% were of lower

socioeconomic group as shown in table 1.

Subjects and Method

Table 1: Socio-demographic

characteristic of

the study

popu-

This

is a retrospective, descriptive study, conducted at

lation

Variable

N

%

the Paediatric Respiratory Clinic of National Hospital

Abuja. The clinic is held once weekly with average

Sex

Male

9

25.0

attendance of 15 patients seen per week. The case fold-

Female

27

75.0

ers of adolescents aged 10- 15 years seen at the clinic

Socioeconomic status

from August 2009 to July 2013 who were diagnosed

High social class

6

16.7

with tuberculosis were retrieved.

Lower social class

30

83.3

333

34

patients (94.4%) were diagnosed after they presented

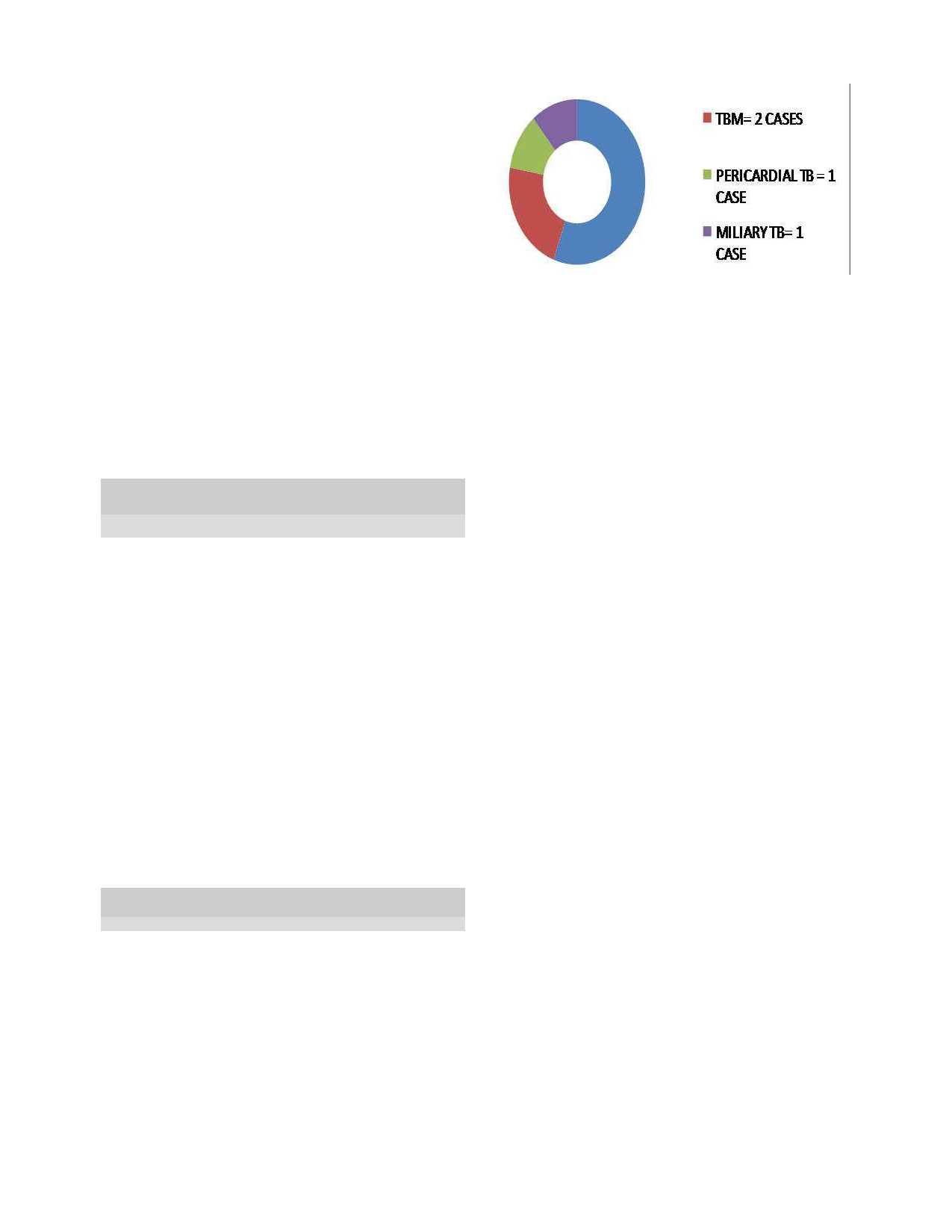

Chart 1: TB

pattern in

adolescent with

retroviral disease

with clinical symptoms while 2(5.6%) were identified

through contact tracing as asymptomatic (latent TB

cases). 17(47.2%) adolescents had a history of contact

with a person with suspected TB while 9(25.0%) had

associated retroviral disease. Thirty two (88.9%) had a

history of BCG given within one month of life. The

most common symptoms identified were cough, weight

loss and fever, while major signs were underweight,

pyrexia

and

chest

findings

(respiratory

distress,

tachpnoea, crepitations, decreased percussion note and

chest expansion); table 2.

Acid- alcohol fast bacillus (AFB) was isolated in 5

(13.9%) and 23 (63.9%) had a raised ESR above 30mm/

hr, Abnormal chest radiograph findings were; wide-

spread lung infiltrate 10 (27.8%), hilar opacities

Discussion

7(19.4%), cavitory lesions 4(11.1%), pleural effusion

3(8.3%) and miliary opacities 1(2.8%). Twenty seven

The study describes the clinical characteristics of adoles-

(75.0%) of the adolescents completed treatment for

cent TB at the National Hospital Abuja. Adolescent TB

tuberculosis, 7(19.4%) were lost to follow up and

accounted for 18.8 percent of cases of TB seen during

2(5.6%) died., while 4(11.1%) had re-treatment for TB

the study period. The female was at greater risk of TB in

due to relapse.

this report. Studies have documented that the prevalence

of

TB in children is higher in girl until between the age

10

and 16 years . The gender disparity becomes evi-

12

Table 2: Common

symptoms and

signs identified

in adoles-

cent TB

dence after fifteen years with a rising rate amongst male

up

till adulthood . Majority of the cases had active dis-

12

Symptoms

N

%

ease. This may be the reason why the prevalence was

Cough

27

75.0

Weight loss

22

61.1

higher in the female since the progression from infection

Fever

18

50.0

to

active disease is more rapid in the female gender early

in

life and the reverse at older age

12,13

Sputum

14

38.9

.

The young girl

Body Swelling (various sites)

7

19.4

has

been shown to have a threefold higher to acquire

Headache

3

8.3

HIV infection when compared to the male of same

Hemoptysis

2

5.6

age. This risk factor for HIV may also contribute to

Swelling in the back

1

2.8

early active disease progression . Other factors that

10

Signs

have been known to account for considerable variability

Underweight ≤ 80%

24

66.7

in

the outcome of M. tuberculosis infection include mal-

Pyrexia

17

47.2

Pallor

16

44.4

nutrition, poor socioeconomic status and immune sup-

pression such as caused by HIV

4,5,14-16

Chest findings

15

41.7

.

Over 60 percent

Hepatomegaly

11

30.6

of

the study populations were undernourished with

Lymphadenopathy

7

19.4

weights 80 percent or less for age and sex. Malnutrition

Gibbus (thoracolumbar)

2

5.6

interferes with the cell mediated immunity (CMI) re-

Neck stiffness

1

2.8

sponse and therefore contributes to much of the in-

creased frequency of TB in impoverished patients .

16

The clinical presentations of TB were; %) pulmonary

TB

(PTB) 22(61.1) and

extra-pulmonary TB 14

The TB rates were highest in the adolescent of lower

(38.9%); table 3

socioeconomic status. The historical association of TB

with low socioeconomic status and poverty had long

been established

14,15

Table 3: Clinical

presentation of

TB in

the adolescents

.

HIV/AIDS–TB co- infection co-

Variable

N

%

existed in twenty five percent of the adolescents. The

dual disease burdens are known to adversely affect the

Latent TB

2

5.6

outcome of each other. HIV impairs the host cellular

Pulmonary TB

22

61.1

Smear positive

5

13.9

immunity to contain TB infection and verse visa. The

Smear negative

17

47.2

combination with HIV co-infection, dramatically com-

Extrapulmonary TB

12

38.9

promises host resistance to TB, leading to high disease

TB

adenitis

4

11.1

prevalence in affected endemic populations that include

TB

meningitis

3

8.3

the adolescent. With the current over half a million ado-

TB

pericarditis

3

8.3

lescent infected with TB as at 2012, the risk for in-

2

Tb

spinal

1

2.8

creasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and

Milary TB

1

2.8

extensively drug-resistant (XDR) MTB strains and the

17

Of

the nine cases with HIV-TB co- infection, 5(55.6%)

more recent occurrence of TDR (totally drug-resistant)

MTB strains, which are virtually untreatable

18

presented pulmonary disease while remaining 4 had

becomes

extra- pulmonary diseases; namely TBM 2; pericardial

a

challenge to all for early detection and treatment of all

TB

and miliary TB one each; in Chart 1

cases of TB.

334

Evidence of late presentation in 94.4 percent of the ado-

the

first years of life, however doesn’t prevent pulmo-

lescents

studied was the presence of clinical symptoms

nary

TB, which is prevalent in the adolescents and

at

time of diagnosis. Such adolescents’ patients would

adults, who mostly spread the infection. A BCG that

have

already contributed to infection transmission espe-

will

prevent progression of latent TB to active disease

cially as they cough with sputum production in the pres-

would be desirable; hence a vaccine that is more effec-

ence

of AFP positive status acting as reservoir of infec-

tive

and safe against TB remains a task. The possible

tion

to contacts. Late diagnosis results from this lack of

role

of a booster or replacement in the ongoing BCG

early clinical suspicion of the disease. Cough was the

trials may in future provide the solution to TB infection

in

the population that includes adolescents .

25

commonest

symptom

in

the

adolescent

while

38.9perecnt were able to produce sputum, unlike the

younger child who most times cannot expectorate volun-

The patterns of TB in adolescents seen are a mixture of

tarily. Cough as a significant symptom was also found

childhood forms and adult patterns in their clinical, ra-

to

be specific in a report by Marais et al

19

in

which a

diological and microbiological findings. Most of the

persistent, non-remitting cough was reported in 15/16

childhood TB forms seen were smear negative PTB

similar to the finding reported by Cruz AT et al.

3

(93.8%) children under 13years with tuberculosis and in

For

2/135 (1.5%) children and young adolescents, without

the extra- pulmonary forms, hilar lymphadenopathy was

tuberculosis, indicating a specificity of 98.5%(135/137)

commonest followed by tuberculous meningitis and

19

.

The use of well-defined symptoms, even in re-

pericarditis occurring in equal proportion. A similar pat-

source limited settings offer some value in the diagno-

tern was also identified in the adolescent with retroviral

sis of childhood and adolescent pulmonary tuberculosis.

disease.

Sputum production with acid-alcohol fast bacillus

(AFB) smear positivity is risk factors for transmission of

Imaging studies such as chest radiograph plays a signifi-

infection among the adolescents and among his peers

cant role in childhood TB diagnosis. A normal radio-

graphic study does not however rule out TB . Abnormal

26

due

to the high social interaction associated with this

age

group. Close to 14 percent were bacteriological con-

chest radiograph findings were mostly widespread lung

firmed cases of TB in the present report. Contact with

infiltrate (27.8 percent), hilar opacities (19.4percent),

person with suspected TB is an important factor for ac-

cavitatory

lesions

(11.1percent),

pleural

effusion

quiring the infection seen in up to 47.2 percent of the

(8.3percent) and miliary opacities (2.7percent). Tradi-

adolescents. Early case finding from screening of con-

tionally, the two radiological patterns of TB manifesta-

tacts of adolescents and adult cases of active cases re-

tions that have been described are the primary TB and

mains a strategy for the prevention and control of TB.

reactivation (post-primary) TB which relate to the pa-

tient immunity . The present study shows a mixed form

27

This also includes the use of isonaizid prophylaxis espe-

cially in under five children exposed to contacts of ac-

of

both primary disease and reactivation TB, though

tive disease and HIV positive persons. All adolescents

primary pattern was more predominant. Children and the

with a contact history must be evaluated with a TST for

immunocompromised persons usually present with fea-

LTBI. Two cases were found to have LTBI in this re-

tures of primary TB which includes; parenchymal infil-

view and treated. The practice of LTBI treatment for TB

trates or consolidation within the lung parenchyma, in-

contacts with a TST size of 10mm and above help re-

volving any pulmonary lobe or segment, hilar lymph

duce progression to disease. This routine use of isoni-

node with or without atelectasis and unilateral pleural

azid preventive therapy (IPT) is an effective and cost-

effusion on the same side of the primary focus of the

TB

. In Reactivation TB, apical consolidations involv-

28

effective intervention among child household contacts.

ing the upper lobe or superior segment of lower lobe are

The use of Bacillus Chalmette –Guerin (BCG) vaccine

commonly seen with other features of cavitation, soli-

tary nodules and military picture min some cases . The

28

was

high among the adolescents.

The BCG vaccine

have been shown to have from zero to 80 percent effec-

primary forms of TB were mostly those of hilar lymph

node enlargement, (52.8 percent). Marias et al reported

29

tiveness in preventing tuberculosis for a duration of 15

years; however, its protective effect appears to vary ac-

that up to 90- 95 percent of primary Tb in children are

cording to geography and the laboratory in which the

hilar lymph node enlargement which could be unilateral

vaccine strain was grown

20,21

.

A 1994 systematic review

or

bilateral and widespread in up to70 percent.

found that the BCG reduces the risk of getting TB by

about 50%; (relative risk (RR) of TB of 0.49 (95% con-

Completion of treatment in TB is a significant part of

fidence interval [CI], 0.34 to 0.70) for vaccine recipients

disease control, as this stops transmission of infection

compared with non-recipients (protective effect of 51%),

from

an active case to contacts. A 75percent complete

and

a protective effect from tuberculous deaths of 71%

treatment rate in the present report was slightly lower

(RR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.53), and a protective ef-

than the reported 85percent national figure (Nigeria

2009 –2013) . A loss to follow up or default from treat-

30

fect for meningitis of 64% (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.18 to

0.70) .

22

BCG is effective against rare forms of severe

ment and poor compliance are risk factors for continuing

childhood TB meningitis and miliary disease, however,

infection transmission in the community with risk for

the variation in protection against common pulmonary

resistance development and drug resistance TB. Lost to

TB

that BCG offers has generally been disappointing in

follow up rate was 19.4percent; which is lower than ear-

trials conducted in the developing world

23,24

.

This pro-

lier report by Jiya et al (36.5%) from Sokoto in north-

west of Nigeria . The Directly Observed Therapy (DOT)

5

tection of BCG for children from severe forms of TB in

335

strategy aim to improve treatment compliance and com-

Conclusion

pletion for the patients through a reliable supervisor of

patients and accurate record keeping. TB treatment in

Tuberculosis remains a significant public health prob-

the adolescent can be a challenge resulting from the di-

lem, particularly in resource limited settings like

verse behavioral, social and economic demography asso-

Nigeria. Late presentation was high in majority of ado-

ciated with the development of the adolescent. This can

lescent as they were symptomatic already before presen-

lead to treatment discontinuation, resulting in perpetua-

tation for diagnosis. A mixed pattern of disease was seen

tion of TB transmission in the community and appear-

in

the adolescent for a disease condition that remains

ance of resistant strains. Death rate among the adoles-

preventable and treatable.

cent was 5.6 percent; similar to the overall TB deaths of

five percent for 2010 (Nigeria) .

31

References

1.

World Health Organization, online

11.

World Health Organization 2011.

20.

Sterne J. A., Rodrigues L. C.,

article; Adolescent health. Link:

The

global plan to stop TB 2011–

Guedes

I. N. Does the efficacy of

http://www. who.int/topics/

2015.

http://www.stoptb.org/

BCG

decline with time since vac-

adolescent_health/en/ (Accessed:

assets/documents/global/plan/

cination? Int.

J. Tuberc.

Lung Dis .

26/10/2013)

TB_GlobalPlanToStopTB2011-

1998; (2) 200–207.

2.

World Health Organization, Ge-

2015.pdf.

21.

Ottenhoff TH, Kaufmann SH. Vac-

neva. Global Tuberculosis Report

12.

World Health Organanization.

cines against tuberculosis: where

2013.Link:http://apps.who.int/iris/

Online article: Gender and Tuber-

are

we and where do we need to

bitstream/10665/91355/1/

culosis. Link: whqlibdoc.who.int/

go? PLoSPathog .

2012; 8(5),

9789241564656_eng.pdf?ua=1

gender/2002/a85584.pdf (Accessed

1002607

(Accessed 26/10/2013)

12/12/2013)

22.

Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey

3.

Cruz AT, Hwang KM, Birnbaum

13.

Hudelson P. Gender differentials

CS,

Wilson ME, Burdick E, Fine-

GD,

Starke JR. Adolescents with

in

tuberculosis: the role of socio-

berg HV, Mosteller F. Efficacy of

Tuberculosis. A Review of 145

economic and cultural factors.

BCG

vaccine in the prevention of

Cases. Pediatr

Infect Dis

J .

Tubercle and Lung Disease

tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the

2013;32(9):937-941

1996;77:391e400.

published literature. JAMA 1994

;

4.

Esiet AO. Action Health Inc. Ado-

14.

Gustafson P, Lisse I, Gomes V,

271(9):698-702

lescent Sexual and Reproductive

Vieira CS, Lienhardt C, Naucler A,

23.

Fifteen year follow up of trial of

H

eal th

in

Ni

geri a.

Wh

y

Jensen H, Aaby P. Risk factors for

BCG

vaccines in south India for

“Adolescent

Sexual and Repro-

positive

tuberculin skin test in

tuberculosis prevention. Tubercu-

ductive Health”. Link: http://

Guinea-Bissau. Epidemiology .

losis Research Centre (ICMR),

www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/

2007; 18:340–7.

Chennai. Indian

J. Med.

Res . 1999;

d e

f a u l t / f i l e s / E s i e t %

15.

Grigg ER. The arcana of tubercu-

110: 56–69

20Presentation.pdf (Accessed

losis with a brief epidemiologic

24.

Rodrigues L. C., Diwan V. K.,

20/11/2013)

history of the disease in the USA.

Wheeler J. G. Protective effect of

5.

World Health Organanization.

Am Rev Tuberc. 1958;78:151–72.

BCG

against tuberculous meningi-

online article: Nigeria- link:

16.

Cegielski JP, McMurray DN.The

tis

and miliary tuberculosis: a meta

www.who.int/countries/nga/en/

relationship between malnutrition

-analysis. Int.

J. Epidemiol .

1993;

(Accessed: 27/11/2013)

and

tuberculosis: evidence from

22:1154–1158

6.

Ibadin MO, Oviawe O. Trends in

studies in humans and experimen-

25.

McShane H. Tuberculosis vac-

childhood tuberculosis in Benin

tal

animals. Int

J Tuberc

Lung Dis.

cines: Beyond BacilleCalmette–

City,

Nigeria .

Ann Trop

Paed

2004 (3):286-98.

Guérin. Philos

Trans R

SocLond B

2001; 21:141-145

17.

Gandhi NR, Nunn P, Dheda K,

Biol Sci. 2011; 366(1579): 2782–

7.

Jiya NM, Bolajoko TA, Airede KI.

Schaaf HS, Zignol M, et al. Mul-

2789.

Pattern Of Childhood Tuberculosis

tidrug-resistant and extensively

26.

Lamont AC, Cremin BJ, Pelteret

In

Sokoto, Northwestern Nigeria.

drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat

RM.

Radiological pattern of Pul-

Sahel Medical Journal

2008;11

to

global control of tuberculosis.

monary tuberculosis in the paediat-

(4):110-113

Lancet 2010; 375: 1830–1843.

ric

age group .

Pediatr Radiol

8.

Wu

XR, Yin QQ, Jiao AX, Xu

18.

Velayati AA, Masjedi MR, Farnia

1986; 16: 2-7.

PB,

Sun L, Jiao WW, et al.

P,

Tabarsi P, Ghanavi J, et al.

27.

Awil PO, Bowlin SJ, Daniel TM.

“Pediatric

Tuberculosis at Beijing

Emergence of new forms of totally

Radiology of pulmonary tuberculo-

Children’s Hospital: 2002-2010

,”

drug-resistant

tuberculosis bacilli:

sis

and HIV infection in Gulu,

Paediatrics , 2012; 130(6):1433-

super extensively drug-resistant

Uganda .

EurRespr J .

1997; 10:

615

1440.

tuberculosis or totally drug-

-618

9.

Winston C, Menzies H. Pediatric

resistant strains in iran .

Chest

28.

Ogbeide O. The radiological man-

and

adolescent tuberculosis in the

2009; 136: 420–425.

agement of tuberculosis. Benin

United States, 2008-2010.

Pediat-

19. Marais

B, Gie

R, Obihara

C, Hes-

journal of postgraduate medicine

.

rics . 2012;130(6) 1425-

1432

seling A, Schaaf H, and Beyers N.

December 2009; 11: 74 – 78.

10.

Lawrence RM. Tuberculosis in

Well defined symptoms are of

children. In: Rom WN, Garay SM,

value in the diagnosis of childhood

eds. Tuberculosis. Boston: Little,

pulmonary tuberculosis .

Arch Dis

Brown, 1996:675-88.

Child. 2005; 90(11): 1162–1165.

336

29.

Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS,

30.

World health Organization online

31.

Nigeria Tuberculosis Fact Sheet.

Hesseling AC, Enarson DA, Bey-

article. Global Health Observatory

United States Embassy in Nigeria.

ers

N. The spectrum of childhood

(GHO).How many TB cases have

Link:http://photos.state.gov/

tuberculosis in a highly endemic

been

successfully

treated?

libraries/nigeria/487468/pdfs/

area . Int

J Tuberc

Lung Dis

2006;

Link:http://www.who.int/gho/tb/

JanuaryTuberculosisFactSheet.pdf.

10:732-738.

epidemic/treatment/en/. (Accessed

2012. (Accessed 10/1/2014).

10/1/2014).